http://www.israelnationalnews.com/Articles/Article.aspx/11517#.T4rkAtlAa-U

Rethinking Early Roman Anti-Semitism

The Jewish Revolt that led to the destruction of the Second Temple is erroneously held to be the start of Roman anti-Semitism, while it is actually more of the same - the belief Jews are sinister, evil and threatening.

From Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

That anti-Jewish prejudice features among Latin authors of the early Principate cannot be doubted.

For example, in the Cena Trimalchionis, which is a part of the satirical novel Satyricon, written during Nero’s reign, two freedmen- Habinnas and Trimalchio- have a discussion on the slaves they own. The former mentions a particular favorite of his, but adds that his “duo vitia” (“two vices”) are that “recutitus est et stertit” (“he is circumcised- i.e. a Jew- and he snores”- Petronius 68.8).

Similarly, in Satire 3, the poet Juvenal, who lived during the reign of the Antonine dynasty at the turn of the second century CE, has a certain Umbricius complain that at Rome, the Jews have taken over the grove of Numa (a symbol of traditional Roman religion).

It has commonly been held that the Jewish Revolt (66-73 CE) marked a turning point in anti-Semitism among Romans. Namely, prior to the Jewish revolt, it has been widely argued that Jews were merely seen as silly rather than sinister or threatening in any way, with, for example, the dietary laws and prohibition against working on the Sabbath sometimes subjected to mockery.

However, I do not find such a view of Roman anti-Semitism tenable. In this context, an incident particularly worthy of consideration is a senatorial decree from 19 CE that ordered practitioners of Egyptian and Jewish rites to either abandon their religion or face expulsion from Italy.

The historian Tacitus (Annals II.85) provides further details:

actum et de sacris Aegyptiis Iudaicisque pellendis factumque patrum consultum ut quattuor milia libertini generis ea superstitione infecta quis idonea aetas in insulam Sardiniam veherentur, coercendis illic latrociniis et, si ob gravitatem caeli interissent, vile damnum; ceteri cederent Italia nisi certam ante diem profanos ritus exuissent.

“And there was a discussion about the expulsion of the Egyptian and Jewish rites, followed by a senatorial decree that 4000 freedmen infected with that superstition and of suitable age should be brought to the island of Sardinia in order to keep a check on the activities of bandits there; and, if any of them perished because of the harshness of the climate, it would be a cheap loss; the rest were to leave Italy unless they abandoned their profane rites before a certain day.”

Not much different then from the decrees issued against Jews in the Iberian Peninsula after the completion of the Reconquista in 1492. The contingent of 4000 freedmen sent to Sardinia is also noted by Josephus and described as a unit of Jewish men only, rather than Egyptians.

The decree was brought on the Emperor Tiberius’ instigation. Josephus recounts an incident whereby four Jewish rascals had apparently persuaded a noble Roman lady who had converted to Judaism- Fulvia- to provide purple and gold for the Temple in Jerusalem, which they then took for themselves; whereupon Fulvia’s husband Saturninus informed Tiberius of the matter.

As for the practitioners of the Egyptian rites, Josephus notes that a noble lady called Paulina (married to another Saturninius) was seduced by a certain Decius, who employed methods of trickery in collaboration with priests of Isis in Rome.

Now, as Heidel convincingly argued in an article published in the American Journal of Philology in 1920, there is a connection between the cases of Fulvia and Paulina. The latter was guilty of “religious prostitution” in Egyptian rites, while the fact that Fulvia was asked to provide purple for the Temple at Jerusalem probably suggested to Tiberius that the Jewish rascals were seeking to make her a “temple prostitute”, a practice inconsistent with Jewish rites.

Nonetheless, if we accept these reasons alone as the justification for the senatorial decree, the harshness seems unbecoming of Tiberius’ characteristic moderatio at the time, which is evident, for example, in his speech to the Senate in 20 CE, urging the senators not to accept the accusations against Piso - who was accused of murdering the Emperor’s adopted son Germanicus, inter alia - as true without proper consideration of the evidence, just because of Tiberius’ grief over Germanicus’ death (Annals III.12).

In a similar vein, speculating on the possible influence of Aelius Sejanus, the Prefect of the Praetorian Guard who later became Tiberius’ “partner in labors” and then consul in 31 CE (only to be executed on charges of treason), is of little help in explaining the nature of the senatus consultum.

Had Sejanus played any part in the Emperor’s instigation of the senatorial decree, it would surely have been documented by Tacitus, who portrayed Sejanus as a reincarnation of the villainous Catiline (Annals IV.1) and was eager to note any instances of the man’s perceived influence on Tiberius’ decision-making.

Instead, it makes sense to begin by noting, as Heidel did, that the decree effectively treats the Egyptian and Jewish rites as identical. The cases of Fulvia and Paulina must therefore have fuelled existing Roman prejudices and suspicions about Egyptian and Jewish religious practices.

The nature of these hostile attitudes can be ascertained from Virgil’s Aeneid, an epic poem written in the first century BCE to celebrate the founding of the Roman race by Aeneas, who was the reputed ancestor of Augustus - the predecessor of Tiberius - and the Julian line. The Aeneid’s influence cannot be overstated, since it became a school-text for educated Romans, and on graffiti at Pompeii and other sites, it is not uncommon to find single-line excerpts from the epic poem.

In an extended description of the Battle of Actium (31 BCE) as depicted on Aeneas’ shield, Virgil depicts the clash as an East vs. West conflict, with Marc Antony and Cleopatra representing the forces of the East that encompass nations like Indians and Arabs, while Augustus leads the armies of Italy. Of particular note are these lines (Aeneid 8.698-700):

omnigenumque deum monstra et latrator Anubis/

contra Neptunum et Venerem contraque Mineruam/

tela tenent.

“All sorts of monstrous gods and the barking Anubis hold their weapons against Neptune, Venus and Minerva.”

It is clear that the gods of Egyptian religion (and perhaps Eastern deities more generally) are represented here as sinister forces that are naturally opposed to the gods of traditional Roman religion.

Hence, on the basis of conflation of Egyptian and Jewish rites, it seems reasonable to conclude that Tiberius and the Senate saw the Egyptians and Jews as somehow a malicious threat to Roman religion and morality in society. The link with Juvenal’s complaint nearly 100 years later about the Jewish takeover of Numa’s grove in Satire 3 could not be more apparent.

The cases of Fulvia and Paulina only vindicated that animosity in the Romans’ minds, and so the only appropriate solution for the Emperor and the Senate was to decree that the Jews and Egyptians in Italy should either convert or leave, with particular furor directed at the Jews, something that is illustrated by the forced conscription of 4000 Jewish men to deal with brigands in the harsh climate of Sardinia.

In short, the senatorial decree of 19 CE suggests continuity in Roman anti-Semitism rather than any crucial turning-point in attitudes because of the Jewish Revolt.

Translations of Latin text are the author’s own.

The IDF Spokesperson’s office is reporting that a delegation of some 60 IDF commanders arrived in Poland on Monday, April 16, as part of the Witnesses in Uniform program. Guided by educators from the Yad VaShem Holocaust Memorial Museum, the officers started a four day study of pre-war Poland, the Holocaust, and contemporary Jewish Polish life. “It is very, very difficult to talk about the six million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust. It’s impossible to comprehend such a number. So the way to make it as comprehensible as possible is through the personal narrative,” said Cpt. Liat Carmi, who oversees the program. This is the 169th Witnesses in Uniform group sent to Poland by the IDF, which plans to send a total of 16 groups just this year. The trip does not focus only the horrors of the Holocaust. “We are talking about a thousand years of Jewish history in Poland,” said Cpt. Carmi. The participants stayed in Warsaw and Krakow, and visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp and other memorial sites. At some of the sites, the soldiers held military memorial services. The participants concluded each day of the journey with a reflective discussion. Commanders explored issues such as how to incorporate the ethical lessons gleaned from the journey into their leadership as commanders, how to convey the history of the Holocaust to the soldiers under their command, and how the Holocaust influences their identities as IDF soldiers.

http://de.rian.ru/infographiken/20120418/263388988.html

G. Grass writes a poem

The Symbol of the Latin Christianity

Guenther Grass in 1944

The Passion inspired by M. Gibson's movie

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/154727#.T4cmOdlAa-U Mel Gibson Accused of Sabotaging Maccabee Film, 'Hating Jews' Hollywood screenwriter accuses Mel Gibson of sabotaging a film based on story of Maccabees; writes letter, "You hate Jews." Rachel Hirshfeld The Hollywood screenwriter Joe Eszterhas has accused Mel Gibson of sabotaging the production of a film based on the story of the Jewish Maccabees, after Warner Bros. decided to cancel the project. Eszterhas wrote an extensive letter accusing Gibson, who was expected to direct the film, of prolonged and unabashed anti-Semitism. "I've come to the conclusion that the reason you won't make The Maccabees is the ugliest possible one. You hate Jews," he wrote. Eszterhas alleged that Gibson had told him the Holocaust was "mostly a lot of horseshit" and that his intention in making The Maccabees was "to convert the Jews to Christianity." "You said the Torah made reference to the sacrifice of Christian babies and infants,” Esterhas asserted. “When I told you that you were confusing the Torah with The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, ... you insisted 'it's in the Torah - it's in there!' (It isn't)."

Christian Communism Logo

Che Guevara and Castro meet

......if Christ himself stood in my way, I, like Nietzsche, would not hesitate to squish him like a worm." Che Guevara. http://www.myspace.com/luciferhorus

Benedict XVi and Castro meet

The Geocentric Dome of Dome of 13th century Bibi-Heybat Mosque

Azeri Language

Foreign Policy magazine reported in an exclusive piece this week that Israel has purchased an Azeri airfield on Iran's northern border, prompting the United States to watch very closely. Journalist Mark Perry wrote the Obama administration is monitoring Israel's relations with Azerbaijan, particularly its military ties. Israel has tightened up its relations with Baku over the past several years, helping Azerbaijan modernize its military with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and becoming its second-largest customer for oil. In particular, the $1.6 billion Israeli deal to jointly manufacture 60 drones of various types with Azerbaijan infuriated Turkey, according to a retired U.S. diplomat quoted in the report. The IDF canceled a $150 million contract to develop and manufacture drones with the Turkish military after Ankara demanded an apology following the Mavi Marmara flotilla attempt to breach Israel's maritime blockade of Gaza. “The Israelis have bought an airfield,” an official told the journalist, “and the airfield is called Azerbaijan.” The Americans believe Israel may use the site as a springboard for an attack on Iran's nuclear plants, or as a landing and refueling spot following one. The site could also be used for aircraft needed for search, rescue and recovery in the wake of an attack.

Lars Vilks, Jesus-pedophile

It is Alciati’s Emblematum Liber (1531) in which the handsome youth Ganymede, who in classical mythology was carried off by Zeus in homosexual mood, has turned into a symbol of the pure soul which finds joy in God, and a later commentator even applied Christ’s command to ‘suffer little children to come to me’ to the story. Consider the case of tailor Jan Tyranowski, aged forty years at the time that Wojtyła met him in the second year of the war. A curious gloss on his bachelordom notes that he had rebuffed the overtures made by various women in his youth. There was an occasional hint of gay ostentation. A picture of him taken around the time he first met Wojtyła reveals him dressed in a white nightgown, sitting bolt-upright in bed between starched lace sheets, like the risen Christ, gazing wide-eyed into the camera.

Benedict XVi kissing sheikh

K. Wojtyla's Ordination as imam-bishop Cracow 1958

Body-soul (Cp. Paul's Spiritual body). Be ready for cosmic journey!

Bonestell-Landing on the Moon

Lunar-lander

Vishnu

Vishnu as Buddha in the sun and Greek Nature

Baal, Shiva, Aten, Odin - Greek god of Nature

The same greenish Hue

The same greenish Hue

Trident Jesus

Angel Gabriel and Virgin Mary

Augustine attacks a problem “whether angels, inusmuch as they are spirits, could have bodily intercourse with women? He reasons on on the ethereal nature of angels, and reaches the conclusion, fortified by many ancient instances, that they can and do. There are, he points out, “many proven instances, that Sylvans and Fauns, who are commonly called 'Incubus' had often made wicked assaults upon women, and satisfied their lusts upon them; and that certain devils, called Duses by the Gauls, are constantly attempting and effecting this impurity” (XV, 23). Thus the great Doctor vindicates the potentiality of the Holy Ghost, in the guise of the angel Gabriel, to maintain carnal copulation with the proliferous yet Ever Virgin .

The Darwinian struggle for Survival at theVatican

The Most Learned canon of Ermland

Such postcard of the Bible Basher are being sold at the Museum of the Cracow Univdersity, where Copernicus studied and wrote poems praising Yeshua which were confiscated by the Vatican

Hegemonikon or the Ruler of von Lauchen's Heliocentrism

In a short passage in von Lauchen's Narratio (p. 465,12; 462,22,35) he refers to the sun not only as God’s steward of nature and king of all distinguished with divine Majesty, but also explains that the sun, like the heart in a body, guides the stars: like a ruler who does not need to go to various towns in order to execute his official duty, so the heart does not have to go to head, to feet, or to other part of the body in order to sustain life. This was a perennial mantra of all heliocentric astrologers throughout the ages. Aztec priests were accused by the Spaniards of performing 50,000 heart sacrifices a year to renew the vital strength of the sun believed to be the heart of the heaven. The Swastika means so many things: life force, rebirth, divine energy, the soul or spirit, "the inner fire" The Hindus have used Swastikas in the Chakras since ancient times. Buddhists are known for using the Swastika and they have called it the 'Buddha's heart'. In the New Testament the heart is called nous, a term denoting also the sun.

A Graphic Rendition of Copernicus's Book

In 1897 one of the best Polish artists and poet Stanislaw Wyspianski published in the magazine Zycie (Life) which he edited, a drawing by a Czech artist Frantisek Bilek unmasking the Renaissance, pagan religion promoted by Copernicus's Latin book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. This drawing reminds us the most revealing fact that Copernicus used the macho-logic of pederastic male supremacy so characteristic of the church to this day, to prove his heliocentrism in terms of pagan religion: “we conceive immobility to be nobler and more divine that mutability and instability, which latter is therefore more appropriate to the earth than to the universe. I add to this that it would seem quite absurd to attribute motion to that which contains and locates, rather than to that which is contained and located – namely, the earth.” For scholastic philosophers woman was animal occasionatus...Mulieres non esse homines. Giordano Bruno stressed that “Nature's imperfect is doubtful to no man. The reason is clear; she is only a woman.” and as an old Italian saying affirms La donna e mobile est. Michelangelo's Zeus plagiarized on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel betrays the same gay misogyny, which we also find in his poem: The love of which I speak has high aspirations Woman is too different; and it all becomes The wise and manly heart to burn for her. One love pulls you heavenwards, the other earthwards; One is located in the soul, the other in the senses, And draws its bow towards things which are low and vile.

Such circles deceived Copernicus into believing in heliocentrism

Death of Nicolaus Copernicus

Aisha Qaddafi seeks asylum in Israel

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/151197#.Tvy9QnoVi-U Report: Qaddafi's Daughter Seeking Asylum in Israel The daughter of former Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, Aisha, is seeking political asylum in Israel, a report says. Elad Benari The daughter of former Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, Aisha, is seeking political asylum in Israel, according to a report on the Intelligence Online website. The report, which was quoted by Yeshiva World News on Wednesday, said that Aisha Qaddafi has hired the services of Nick Kaufman, a former prosecutor assigned to the Jerusalem District Prosecutor’s Office to advance her cause. This past August, when Libyan rebels took over the Qaddafi family compound in the capital Tripoli, Aisha fled Libya together with her mother and a number of brothers. They found refuge in Algeria, where Aisha has since given birth to a son. Last month, she called on Libyans to topple the new government and urged them not to forget her father. According to the report, she now fears that local government officials will eventually give into demands from the new Libyan regime and she will face extradition. Friends of Aisha in Europe, according to the report, said she believes the only country where she will feel safe is Israel, and she is advancing efforts towards obtaining political asylum with the realization that her chances of receiving asylum are not particularly good.

The Committee of 300 or British CHEKA

This committee of 300 is modeled after the British East India Company's Council of 300, founded by the British aristocracy in 1727. Most of its immense wealth arose out of the opium trade with China. This group is responsible for the phony drug wars here in the U.S. These phony drug wars were to get us to give away our constitutional rights. Asset forfeiture is a prime example, where huge assets can be seized without trail and no proof of guilt needed. (See the video The Truth About the Fraud and Bank of America foreclosure) Also the Committee of 300 long ago decreed that there shall be a smaller-much smaller-and better world, that is, their idea of what constitutes a better world. The myriads of useless eaters consuming scarce natural resources were to be culled. Industrial progress supports population growth. Therefore the command to multiply and subdue the earth found in Genesis had to be subverted. This called for an attack upon Christianity; the slow but sure disintegration of industrial nation states; the destruction of hundreds of millions of people, referred to by the Committee of 300 as "surplus population, " and the removal of any leader who dared to stand in the way of the Committee's global planning to reach the foregoing objectives. Not that the U.S. government didn't know, but as it was part of the conspiracy, it helped to keep the lid on information rather than let the truth be known. Queen, Elizabeth II, is the head of the Committee of 300. The Committee of 300 looks to social convulsions on a global scale, followed by depressions, as a softening-up technique for bigger things to come, as its principal method of creating masses of people all over the world who will become its "welfare" recipients of the future. The committee appears to base much of its important decisions affecting mankind on the philosophy of Polish aristocrat, Felix Dzerzinski, who regarded mankind as being slightly above the level of cattle. As a close friend of British intelligence agent Sydney Reilly (Reilly was actually Dzerzinski's controller during the Bolshevik Revolution's formative years), he often confided in Reilly during his drinking bouts. Dzerzinski was, of course, the beast who ran the Red Terror apparatus. He once told Reilly, while the two were on a drinking binge, that "Man is of no importance. Look at what happens when you starve him. He begins to eat his dead companions to stay alive. Man is only interested in his own survival. That is all that counts. All the Spinoza stuff is a lot of rubbish." (Dr. John Coleman)

Black SS-Pope

Pope John Paul II's 'Breviary'

Workers-priests

The first article the young father karol Wojtyla published in the Cracow Universal Weekly upon his return from Italy was titled Mission de France and dealt with the movement of the fashionable workers-priests whio actually were communist infiltrators in the Catholic church

Communist Pope

Superhubris

Very Evil Pope

Lethal Mix AIDS and Alkoholism

Theology of the Body or by boobs and by crux

Theology of the Body or from Palestine with Love

Justin Martyr: Jesus is an erected phallus, like Egyptian Min

The Phallic Mosque in Jerusalem

Symbol of Islam

Karl Marx monument viewed from back looks like a phallus

Aldous Huxley called Darwin's bloody-fanged bulldog in his book Ends and Means, 1946, p. 70 explains enthusiastic reception of evolutionism as follows: “I had motives for not wanting the world to have meaning...The liberation we desired was.;..from a certain system of morality. We objected to the morality because it interfered with our sexual freedom.” Maurice Samuel suggested that Jew-hatred sublimates the yearning of Christians for the freedoms of the pagan world. They resent Christian morality as the straight jacket that inhibits the release of their pagan instincts that emerge occasionally in their consciousness. Scientist Zaborovsky wrote in one of his works devoted to baboons: “Baboons stand out among other apes for their sexual lustfulness. The phallus of a male baboon is almost always erected, like the phalluses of the martyrs enjoying their 72 virgins.If a male boon is locked alone in a cage, he will die from his unsatisfied desire to copulate; The smell of a female can drive a male baboon to insanity.” A baboon with an erected penis was a divinity in ancient Egypt.” The god Min depicted with an erect phallus was his human counterpart.

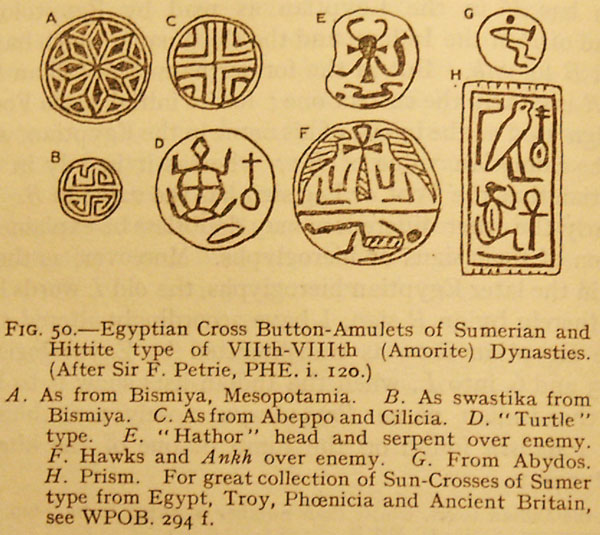

Hittite, Phoenician, Kassi cult of the Sun and Cross

The Nicene, evolving cat of Massachussetts

The Nicene Jesus in Trinity

UNSC rejects Palestine's bid for membership

The UN Security Council Committee for Admission of New Members was unable to endorse Palestine's bid to join the ranks of this international organization. The draft report circulated at the UN headquarters in New York said that the votes of the committee's 15 Member States were divided. On October 31, Palestine was granted full UNESCO membership. During the vote, it received the support of 107 countries, including Russia. Voting "against" were 14 states, in particular, the U.S. and Israel. (Reuters)

An Italian Poster on the funeral day of pope JP2

Irish Embassy to the Vatican to be Closed

The Government has decided to close Ireland's embassies to the Vatican and Iran as well as its representative office in Timor Leste. In a statement this evening, Tánaiste Eamon Gilmore said that the decision followed a review of overseas missions carried out by the Department of Foreign Affairs, which gave "particular attention to the economic return from bilateral missions".

Swastika - the Perennial symbol of sun gods

The Phoenician Origin of Britons, Scots & Anglo-Saxons - Lawrence Austine Waddell Orig. pub. by Williams & Norgate, 1924 2nd ed., 1925

Allah is the sun god. He is Mar Alah, or the sun god Surya

Ethereal body in Hindu religion

Saint Paul, an ancient klansman

Obama, the Enabler

Qaddafi's Corpse

After his death, the corpse of the former tormenter was put on display in Misrata. People posed for pictures with Gadhafi's dead body. Stripped down to the waste, it was passed from house to house like a trophy until it finally arrived in the front room of a private residence in the so-called African Market on Friday An air-conditioning unit hangs on the wall. The body lies on a thin mattress on the floor. The head is tilted a bit to the left, and the arms lie close to the body, which is only covered by a pair of brown pants. At the entrance, people are fighting to get in. In a mix of voyeurism and the need for certainty, everybody wants to get one last look of the body and take a picture of it. http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,793612,00.html

OccupyAurora Protest in Sankt Petersburg

http://de.rian.ru/photolents/20111021/261076161.html Sieben Tage in Bildern: 15. bis 21. Oktober 2011

The relics of John Paul II in Odessa

http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/10/24/59222975.html The relics of Pope John Paul II have been brought to the Catholic Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in Odessa. This is a particle of fabric, soaked with the pontiff’s blood. The relics were received by Bishop Bronislaw Bernatskij from the former personal secretary to the Pope, Stanislaw Dziwisz. They will be stored in a special reliquary in the form of a crown of thorns.

The Afghan Crucifix: Jesus died al kiddush ha-Shem

Wernher, shoot him down

Death to Assad

http://de.rian.ru/opinion/20111021/261075526.html 17:51 21/10/2011 Inspired by Gaddafi’s death, Syrian oppositionists set mass riots in many places all over the country on Friday, shouting out: “Gaddafi is dead, now it’s Bashar al-Assad’s turn!” (Bashar al-Assad is Syria’s current president.) Syrian human rights defenders say that on Friday, 16 demonstrators were shot by the police, and, in total, over 3,000 civilians were killed in Syria since riots began in March. The government, in its turn, calls the oppositionists “bandit groups” and claim that these “bandits” are killing Syrian servicemen. (IF)

Nazi and fascist Dictators

Farrakhan with Rev. Pfleger

When Farrakhan was asked at a press conference whether he truly thought Hitler was “great” he responded, “I don’t think you would be talking about A. Hitler forty years after the fact if he was some minuscule crackpot that jumped up on the European continent. He was…a great man, but also wicked…wickedly great.” Referring to Hitler’s as “great” twice in the space of a few weeks sealed Farrakhan’s fate as the New Demon, the Great Hater, the Next Fuehrer. Further condemning him was a June 1984 statement that Israel will “never have…peace, because there can be no peace structured on injustice, lying, and deceit and using the name of God to shield your dirty religion under his holy and righteous name.” Using boilerplate anti-Jewish imagery – “bloodsuckers,” “Jews control the media,” Israel is “an outlaw” nation, a people “cloaking themselves in the robes of god, but who are in fact members of the synagogue of Satan” – all of which Farrakhan presented as irrefutable “truths,” the NOI leader demonized an entire people, while simultaneously denying he was anti-Semitic. As a child, he received training as a violinist. At the age of six, he was given his first violin and by the age of 13, he had played with the Jesuit Boston College Orchestra and the Boston Civic Symphony. A year later, Walcott went on to win national competitions, as well as the Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour. He was one of the first blacks to appear on the popular show. In Boston, Farrakhan attended the prestigious Boston Latin School. The school symbol is Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome! and English High School, graduating from the latter1. He attended college for two years at Winston-Salem State University teachers college, but left to continue a career as an entertainer. In the 1950s, Farrakhan became an up-and-coming calypso singer. He recorded several calypso albums under the name "The Charmer." [1] In 1955, while headlining a show in Chicago entitled "Calypso Follies," he first came in contact with the teachings of the Nation of Islam. Check out this ARTICLE Called: “Louis Farrakhan claims he is both a Muslim and a Christian (Catholic)” Quote from article, “A packed house welcomed Minister Louis Farrakhan to St. Sabina Catholic Church on Friday night with a standing ovation and cheers for his health.

M. Gibson receives a honorary degree from a Catholic Notre Dame University

The Hate Propaganda sposored by theVatican

Gilad at last home

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/148884#.Tp27V3JiK-U President Shimon Peres met German mediator Gerhard Conrad Tuesday and thanked him for his role in enabling the Shalit deal. Conrad was accompanied by senior members of German intelligence and representatives of the German government. "The entire nation of Israel is holding its breath in excitement because Gilad Shalit is the son of all of us. I wish to thank you as the president of the state of Israel in the name of the nation in Israel, for your personal contribution to the long and protracted negotiations that ended with the release of Gilad Shalit. "You carried out the negotiations in circumstances that were not simple and in a complex reality with professional, smart and devoted work. We all know the depth of your commitment to the release of Shalit."' Peres also thanked German Chancellor Angela Merkel for supporting the negotiations and said that she "proves through her actions the depth of the friendship and strategic relations between the two countries." Conrad said the compliments "embarrassed" him. "Both sides had to make decisions that were not simple and I am glad both sides made decisions. After all it was a very difficult challenge, sometimes demanding and frustrating, but I am filled with excitement and satisfaction when I see Gilad Shalit returning home, together with you."

Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon to me wishing me a happy New Year

Yes, I agree with FM of Israel that it Was Almighty God who gave the Prmised Land to his People and that the ultimate decisions always belong to Him and not to the Quartet or Quintet, or the UN no matter how powerful these entities might be. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-10/17/c_131196403.htm BEIJING, Oct. 17 (Xinhua) -- China on Monday called for other countries to respect its agreement with Vietnam on maritime issues. "The fact that China and Vietnam have agreed to settle maritime disputes through negotiations has nothing to do with a third party. We expect the third party to respect the efforts by the countries concerned to resolve the disputes through negotiations," Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin said at a daily press briefing. Liu's comments came after it was reported that the Philippines opposed the latest China-Vietnam joint statement and called for a multilateral approach, rather than a bilateral agreement, to resolve disputes concerning the South China Sea. "China-Philippines maritime disputes can only be resolved through direct negotiations between China and the Philippines, a stance the Philippines is quite clear about," Liu said.

Enough is enough

Israel is going to build on its experience of peace dealing with Jordan and Egypt by seeking peace with the Palestinians through direct talks with them. Speaking on Sunday, Foreign Minister Avigdor Liberman said big-power mediation attempts by Russia, the United States, the United Nations and the European Union are counterproductive and stir misleading speculation in the media. He also advised the quartet to forget about the Palestinians and Israel. (IF)

Baal, Ashera with the pagan symbol of Trinity

“The first fundamental law Of the Universe”, Gurdijeff says “is the law of three forces, or three principles, or, as it is often called, the law of three.' according to which 'every action, every phenomenon in all worlds without exception, is the result of a simultaneous action of three forces – the positive, the negative, and the neutralizing.

Jesus with the Pagan Symbol of Trinity

We believe in one God father Almighty maker of all things, seen and unseen: And in one Lord Jesus Christ the Son of God, begotten as only-begotten of the Father, that is of the substance (ousia) of the father, God from god, Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten not made, consubstantial (homoousios0 with the Father, through whom all things came into existence, both things in heaven and things on earth: who for us men and for our salvation came down and was incarnate and became man, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended into heavens, is coming to judge the living and the dead: And in the Holy Spirit. But those who say 'there was time when he did not exist' (Arius and his followers), and 'Before being begotetn he did not exist' , and that he came into being from non-existence, or who allege that the Son of god is of another hypostasis or ousia, or is alterable or changeable, these the Catholic and Apostolic Church condemn.

Putin meets Hu Jintao Oct. 12, 2011

Paul and Nancy

LONDON- Former Beatle Paul McCartney was set to marry American heiress Nancy Shevell in London on Sunday and will serenade her with a song written in her honor, media reports said. The couple went to a local synagogue on Saturday where Shevell, who is from a prominent New York Jewish-American family, received a blessing, before dining at a floating Chinese restaurant with family and friends.

The Kurds in Syria demand an independen state of their own

Who will solve this Problem? There are also milions of Kurds in Iraq, Iran. And yet the powers disregard their "human rights" Im sure, that God won't forget them. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/world/2011-10/19/c_131200697.htm ANKARA, Oct. 19 (Xinhua) -- Twenty-four members of the Turkish security forces were killed and 18 others injured in Turkey's southeastern province of Hakkari early on Wednesday in simultaneous attacks carried out by the outlawed Kurdish Workers' Party (PKK), the private Dogan news agency reported. PKK rebels attacked several military and police buildings and killed 24 soldiers and police officers in several locations in the predominately Kurdish province near the Iraqi border, a day after they killed five police officers and three civilians in Bitlis province in southeastern Turkey, the report said. A Kurdish news agency said the Turkish forces has crossed into Iraq in pursuit of the PKK members, who has recently intensified attacks on Turkish troops, police and civilians. Turkish officials vowed to reciprocate with absolute determination. Listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States and the European Union, the PKK took up arms in 1984 to create an ethnic homeland in southeastern Turkey. More than 40,000 people have been killed in conflicts involving the PKK during the past over two decades.

A. Hitler's letter of 1919 postulating destruction of Jews

Who is Confucius but Moses speaking Chinese?

Yassir Arafat Dying of AIDS

Y. Arafat was a pedophile

The Aryan, heliocentric Ruler of Canaan

The cross and the fire, the latter, the emblem of the sun were both symbols of the Hindu god of fire Agni. The Hindu term jamad agni denotes a sage who knows the identity of god and fire, like the authors of the new Roman Cathechism. Fire is heat – the central point, the perpendicular ray represents the male element or spirit, and the horizontal one the female element – or matter. Spirit (also called logos spermatikos) vivifies and fructifies the matter, and everything proceeds from the central point, the focus of Life, and Light, and Heat, represented by the terrestrial fire. Interestingly, Taunay’s Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, (s.d. 1818 Nice, Préfecture, No. 175) shows John the Baptist holding a cross in his right hand. Jesus in his baptism is hailed from Heaven as the beloved son and the only begotten of the Father, God; the Holy Spirit is represented by a dove. This dove, in later development, became the third member of the Holy Trinity i.e. third person one with the Father. Jesus in his baptism became what Cardinal K. Wojtyla called in his Lent Sermons for Pope Paul VI Sign of Contradiction according to Lk 2:34 “Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising against many in Israel; and for a sign which shall be spoken against.” Because this dove is derived from the myth of the sun god Apollo (see attached picture). Similarly, Horus in his baptism made his transformation into the beloved son and only begotten of the father; the Holy Spirit, represented by a bird. During nightly meeting with Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews Jesus lectures on how a “man can be born again” in order that he could “see the kingdom of God.” (John 3:3). According to v. 5 this rebirth (see below) comes from “water and spirit” symbolized by two bars of the cross as described above. Accordingly, in another Sign of Contradiction Jesus taught: “If you have ears, listen to what the Spirit says to the churches. I will let everyone who wins the victory eat from the life giving tree which is in the midst of the paradise of God”(Rev. 2:7), which nixed the warning of the God of the Hebrew Bible: “…but of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God said: Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest you die’ (Gen. 3:3). God who inspired the Hebrew Bible knew that many minds, hungering after proofs of immortality, are fast falling into fanaticism and fanatics are governed rather by imagination than judgment. Contemporary Israelis blown apart in buses by a Palestinian suicide/homicide bombers are victims of this insane imagination.

Mussolini, a sculpture by Polish artist S. Szukalski

The Jedwabne Monument in Poland Vandalized

Map of the Indo-British Empire of the Sun

Aria in the Behistun Inscription

The earliest epigraphically-attested reference to the word arya occurs in the 6th century B.C. Behistun inscription, which describes itself to have been composed "in arya [language or script]" (§ 70). As is also the case for all other Old Iranian language usage, the arya of the inscription does not signify anything but "Iranian".

Aria on Waldseemuler's map o 1507

Madison Grant's Nordic Theory

Grant is most famously the author of the popular book The Passing of the Great Race in 1916, an elaborate work of racial hygiene detailing the "racial history" of Europe. Coming out of Grant's concerns with the changing "stock" of American immigration of the early 20th century (characterized by increased numbers of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, as opposed to Western and Northern Europe), Passing of the Great Race was a "racial" interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, stating race as the basic motor of civilization. Similar ideas were proposed by Gustav Kossinna in Germany. Grant promoted the idea of the "Nordic race"—a loosely defined biological-cultural grouping rooted in Scandinavia—as the key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book was The racial basis of European history. As an avid eugenicist, Grant further advocated the separation, quarantine, and eventual collapse of "undesirable" traits and "worthless race types" from the human gene pool and the promotion, spread, and eventual restoration of desirable traits and "worthwhile race types" conducive to Nordic society: A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him, or else future generations will be cursed with an ever increasing load of misguided sentimentalism. This is a practical, merciful, and inevitable solution of the whole problem, and can be applied to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased, and the insane, and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings rather than defectives, and perhaps ultimately to worthless race types. ” In the book, Grant recommends segregating "unfavorable" races in ghettos by installing civil organizations through the public health system to establish quasi-dictatorships in their particular fields. He states the expansion of non-Nordic race types in the Nordic system of freedom would actually mean a slavery to desires, passions, and base behaviors.

Moscow - Beijing Express

URUMQI, Sept. 3 (Xinhua) -- Chinese Vice Minister of Commerce Zhong Shan said member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) should consider setting up a free trade agreement (FTA) which, once in place, would cover about three fifths of the Eurasia's landmass. Zhong told a forum at the on-going China-Eurasia Expo in the northwestern city of Urumqi that such a FTA will further facilitate trade and create a sound environment for pragmatic regional economic cooperation. "Eying the trend of economic globalization, Beijing considers that SCO members should discuss the possibility of setting up a FTA within the organization at a proper time," the vice minister said. The SCO, founded in Shanghai in June 2001, groups China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The six member states cover an area of over 30 million square kilometers, or about three fifths of Eurasia, with a population of 1.455 billion, about a quarter of the world's total. Trade among SCO members grew seven times over the past decade to reach 8.4 billion U.S. dollars in 2010, Zhong said, adding that significant progress had also made in the cooperation on energy, transportation, and telecommunications. In November 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev presented a draft proposal on a new European security agreement as an alternative to NATO. The document called the United States, the European Union and Russia the "three branches of European civilization," and assigned priority to the UN's role in international affairs.

A New Huge Free Trade Zone in the Making

14:35 03/09/2011 Leaders of a post-Soviet alliance called on Saturday for signing a delayed free trade agreement and peacefully resolving conflicts in their final statement rounding up the summit. Leaders of the CIS alliance, which includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Moldova, and Uzbekistan, gathered in Dushanbe, the Tajik capital. Ukraine was also represented at the event though officially it is not a member. "Considering the sustainable growth in foreign trade, CIS member states are seeking to develop economic cooperation based on the CIS economic development strategy until 2020," the statement said. The key goal at the moment is to form a free trade zone, the document said. In May, the CIS Economic Council decided to work further on the draft agreement on free trade in the CIS. It was later discussed by the CIS premiers who failed to reach an agreement. The next meeting of CIS premiers will be held in October.

The Aryan Christ of the Jesuits

In January 1933, the Belgian mathematician and Catholic priest Georges Lemaitre traveled with Albert Einstein to California for a series of seminars. After the Belgian detailed his Big Bang theory, Einstein stood up applauded, and said, This is the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of creation to which I have ever listened. Lemaitres theory, the idea that there was a burst of fireworks which marked the beginning of time and space on a day without yesterday, was a radical departure from prevailing scientific understandings, though it has since come to be the most probable explanation for the origin of the universe. (In other words, a Jesuit was behind the embarrassing doctrine of the "Big Bang" theory. -TR )

The Cosmic dance of Big Bang

"I learned much from the Order of the Jesuits", said Hitler... "Until now, there has never been anything more grandiose, on the earth, than the hierarchical organization of the Catholic Church. I transferred much of this organization into my own party... I am going to let you in on a secret... I am founding an Order... In my "Burgs" of the Order, we will raise up a youth which will make the world tremble... Hitler then stopped, saying that he couldn't say any more.." Hermann Rauschning, former national-socialist chief of the government of Dantzig: "Hitler m'a dit", (Ed. Co-operation, Paris 1939, pp.266, 267, 273 ss).

Bestiality in Hinduism

Erotic Artwork on the facade of the Lakshmana temple

Buddhist Solar Trinity

Christian Copy of the Buddhist Solar Trinity

the Marriage of Philology and Mercury

This single encyclopedic work, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury"), sometimes called De septem disciplinis ("On the seven disciplines") or the Satyricon,[2] is an elaborate didactic allegory written in a mixture of prose and elaborately allusive verse, a prosimetrum in the manner of the Menippean satires of Varro. The style is wordy and involved, loaded with metaphor and bizarre expressions. The book was of great importance in defining the standard formula of academic learning from the Christianized Roman Empire of the fifth century until the Renaissance of the 12th century. The eighth book of M. Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii describes a modified geocentric astronomical model, in which the Earth is at rest in the center of the universe and circled by the moon, the sun, three planets and the stars, while Mercury and Venus circle the Sun.[4] This view was singled out for praise by Copernicus in Book I of his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. Dedicating the work to a powerful patron was also usual practice and Paul III, the pope to whom De revolutionibus was addressed, had previously been the recipient of the dedication in another astronomical work. In 1538, Girolamo Fracastoro had produced his own, rather less radical, reform of Ptolemy and seen fit to offer it to the same Pope The celestial marriage described by M. Capella inspired two best-known scientists of the Renaissance era: Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553) physician and poet, and N. Copernicus (1473-1543) also physician, poet and astrologer. In his long poem, Fracastoro argues that the infecting semina of syphilis may arise from poisonous emanations sparked by planetary conjunctions. He even invokes a linguistic parallel between transmission of syphilis by sexual contact (coitus) and the production of bad seeds by planetary overlap in the sky, for he describes the astronomical phenomenon with the same word, as “coitum et conventum syderum” (the coitus and conjunction of stars), particularly “nostra trium superiorum, Saturni, Iovis et Martis” (our three most distant bodies: Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars). In other words, Fracastoro was led in his speculations by the perennial astrological principle: “As Above, so Below”. And so was Copernicus. The expression “family of stars” suggests what Fracastoro described as “coitum et conventum syderum” and what follows logically polytheism! In one of the Thanksgiving Psalms from Qumran caves, God is addressed as “the Prince of the gods and the King of the venerable ones, and the Lord of every spirit, and the Master of every work.” This god whose rays the Essenes avoided to offend while defecating is the same sun god whom Copernicus describes as “sitting on the royal throne and reigning the surrounding family of stars.” E. Halley found the same astrological belief in Newton’s work. In his preface to the first edition of “Principia” he wrote some complimentary verses in Latin, ending in the line, “Nec fas est proprius mortali attingere divos” (t is not allowed to any mortal to come closer to the gods).

Peter-Mercury in St. Peter's Church

The Geocentric Flag of the African Union

Sundisk from Alacohuyuk (Anatolia)

Three crosses in circles stand for Trinity

The True Sexist Palestinian

Kill Jesus

The Symbol of the Aryan Trinity AUM within the sun god Surya

A. Hitler's Historical Jesus under the radiant sun

St. Paul's Golden "Calf"

These Aryan people worshipped nature; the sun, moon, sky, and earth as a comparison of ancient religions and mythology in the land peopled by Aryans, demonstrates. Their chief object of adoration was the Sun. To this race, in the infancy of its civilization, the Sun was not a mere luminary, but a Creator, Ruler, Preserves, and Savior of their world as they knew it. Around the Sun these people would develop a religious doctrine which finds its origin in the Sun and its influence upon mankind. Such is called "Astro-Theology". Their reasoning led them to believe that the Sun was the product of the Sky god; the Heavenly Father. This "offspring of the Sky-god" was none other than "the Son of the Sky", or that the Sun was the "Son of the Heavenly Father", and that the immaculate virgin, the Earth (sometimes it was the dawn or the night), was the Mother of the Sun. Hence we have the Virgin, or Virgo, as one of the signs of the Zodiac. The zodiacal sign of Aires was anciently known as the Lamb; consequently, when the Sun made the transit of the equinox under this sign, the Sun was called the "Lamb of God." Later when the Sun was personified as "the Son" then the "Son was the Lamb of God."

The Whore of Babylon behind the Holocaust

Behind the Holocaust

Holy Ghost in the shape of swastika

A Christian from the catacombs with swastikas

the Papal Key to the Concordat with A. Hitler

From Emperor Hadrian to Pope Pius XII

Hadrian attempted to root out Judaism, which he saw as the cause of continuous rebellions, prohibited the Torah law, the Hebrew Calendar and executed Judaic scholars (Ten Martyrs). The sacred scroll was ceremonially burned on the Temple Mount. In an attempt to erase the memory of Judaea, he renamed the province Syria Palestina (after the Philistines), and Jews were forbidden from entering its rededicated capital. When Jewish sources mention Hadrian it is always with the epitaph "may his bones be crushed" (שחיק עצמות or שחיק טמיא,Blotting out the handwriting of ordinances that was against us, which was contrary to us, and took iot out of the way, nailing it t his cross. There is an ominous historical parallel; the Vatican was the first state to extend recognition to the neo-pagan Bolshevik regime (1922). Soon thereafter Pope Pius XI disbanded Partito Popolare, forerunner of the present Democrazia Cristiana (Pius XII nailed the Bible to the Cross) and forced its leader to exile. Similarly, and for the same reason the present Democrazia Cristiana disappeared from the political scene of Italy during the pontificate of John Paul II. Why? Because Christian teaching stays in the way of a new Palestinian State.29. And first of all, by the death of our Redeemer, the New Testament took the place of the Old Law which had been abolished; then the Law of Christ together with its mysteries, enactments, institutions, and sacred rites was ratified for the whole world in the blood of Jesus Christ. For, while our Divine Savior was preaching in a restricted area - He was not sent but to the sheep that were lost of the House of Israel [30] - the Law and the Gospel were together in force; [31] but on the gibbet of His death Jesus made void the Law with its decrees [32] fastened the handwriting of the Old Testament to the Cross, [33] establishing the New Testament in His blood shed for the whole human race.[34] (MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI , ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII . 1943) ”L’Osservatore Romano” proclaimed: “True anti-Semitism is and can be in substance nothing other than Christianity, completed and perfected in Catholicism.” J. Streicher, the publisher of anti-Semitic and pornographic Der Stürmer considered the Bible pornographic literature and had no use even for Christ because he was a Jew. An article published in Der Stürmer on March 19, 1942 complained that Christian teaching had stood in the way of a “racial solution of the Jewish question in Europe” and quoted as a rallying call the Führer proclamation: “the Jew will be exterminated.” To kill the “Christian teaching that had stood in the way of extermination of the Jews” the Nazis commemorated the four hundredth anniversary of publication of Copernicus’s The Revolution in 1943 by issuing a post stamp in the occupied part of Poland called Generalgouvernement bearing Copernicus’s likeness (the young seminarian K. Wojtyla used to put this stamp on his letters). At the same time book entitled Kopernikus Forschungen was published in which an author argued that Copernicus once and for all removed from human hearts belief in the Bible. Let me remind here that already in 1945, so to say on the heels of the retreating Nazis, a University named in honor of Copernicus was organized in Torun. I still remember from my grammar school “scientific” propaganda matching that being proclaimed in the Palestinian schools. http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/146933#.Tk6mfF1iLmV PA Vows to Erase 'Filth,' Build Arab Homes at Western Wall

Why did he fail to marry?

At the time the position of the Pharisees was that “it was a man's unconditional duty to marry.” The contemporary Rabbi Eliezer is credited with stating: “Whoever does not engage in procreation is like someone who spills the blood.” So if Jesus was unmarried, as the Church would have us believe, why didn't his Pharisees opponents – of which there were many noted in the New Testament – use his unmarried state as a further criticism of him and his teachings?> Why didn't the disciples who were married ask Jesus to explain his failure to marry?

Iraq buys Czech fighters

Iraq will buy 36 Czech fighters L-159 ALCA

Bonaparte's proclamation to the Jews of Africa and Asia During the siege of Acre in 1799, the main French newspaper during the French Revolution, Le Moniteur Universel, published on 3 Prairial, Year VII (French Republican Calendar, equivalent to 22 May 1799) a short statement that: "Buonaparte a fait publier une proclamation, dans laquelle il invite les juifs de l'Asie et de l'Afrique à venir se ranger sous ses drapeaux, pour rétablir l'ancienne Jérusalem; il en a déjà armé un grand nombre, et leurs bataillons menacent Alep."[1] This has been translated in English as: "Bonaparte has published a proclamation in which he invites all the Jews of Asia and Africa to gather under his flag in order to re-establish the ancient Jerusalem. He has already given arms to a great number, and their battalions threaten Aleppo."

Reversed Evolution of Nebuchadnezzar

The Dying children in Warsaw Ghetto

There was no Powerful Quartet Then. No Freedom Flotillas. No Thousands of Letters of Support aborad a Audacity of Hope. No American Jews sending letters of protest to Haj Amin in Berlin demanding to stop his genocidal propaganda...

The Warsaw Ghetto Children

the Pope did not beg God to show Mercy. No American Charity organization ever sent millions or billions of dollars to IRC, to help those starving children etd.. Nobody dared to ask for a homeland for the Jews. Not even profesional neighbors' lovers... Jesus Christ sat on his Father's right hand and refused to talk to his deputy in the Vatican... One Million Jewish children died in Auschwitz and the powerful B52 bombers did not drop one bomb to prevent more Jewish children to be sent to the ovens. That's the world we are living in. The smell of Arab oil suffocated every humananitarian venture.

Palestinian Children play in water in Gaza Strip

Ammi Hai

M. Gottlieb: Yom Kippur in the Cracow Alte Shul

Obama Scraps the Global War on Terror

The Obama administration has ordered an end to use of the phrase "Global War on Terror," a label adopted by the Bush administration shortly after the September 11, 2001 attacks, the Washington Post reported on Tuesday. In a memo sent this week from the Defense Department's office of security to Pentagon staffers, members were told, "this administration prefers to avoid using the term 'Long War' or 'Global War on Terror' [GWOT.] Please use 'Overseas Contingency Operation.'" http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2009/03/25/obama-scraps-global-war-terror-overseas-contingency-operation/

H. Clinton has a Crush on Al Jazeerah

Hillary Clinton is so over American news outlets. Speaking to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Thursday, the Secretary of State spoke the virtues of Arab news service Al Jazeera. "You've got a global — a set of global networks — that Al Jazeera has been the leader in, that are literally changing people's minds and attitudes ... Viewership of Al Jazeera is going up in the United States because it's real news." And she's totally breaking up with Stateside media outlets. "You may not agree with it, but you feel like you're getting real news around the clock instead of a million commercials and, you know, arguments between talking heads, and the kind of stuff that we do on our news," Clinton said. "Which, you know, is not particularly informative to us, let alone foreigners." Ooh, burn! http://nymag.com/daily/intel/2011/03/hillary_clinton_has_a_crush_on.html

Muslim-Obama

Perfect Together

Amin Al-Husseini becomes prominent member of Muslim Brotherhood. He sees the Wahhabi concept of Islamic Jihad as a key tool to rally pan-Islamic support to further his agenda of Pan-Islamic take-over. The Muslim Brotherhood now under Husseini’s influence, becomes the main vector of hatred against the West and the Jews: the Arab World, which includes Palestine, must be free of any non-Islamic faith. Therefore, Jews and Christians have no claim to any part of the Middle East or of the Arab World. Amin Al-Husseini is one of the primary founders and the inspiration of Arab League. Goal is to reinforce Wahhabi vision of Pan-Islamic unity. Founding countries are: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Yemen. After World War II, Amin Al-Husseini was visited multiple times in Beirut by Hitler’s Swiss banker, Francois Genoud. Genoud finances the ODESSA network. He sponsors Arab Nationalism with Nazi money. In Cairo and Tangiers, Genoud sets up import-export company called Arabo-Afrika, which is a cover to disseminate anti-Jewish and anti-Israeli propaganda.Genoud sets up Swiss bank accounts for North African liberation armies of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. In partnership with Syria, he sets up Arab Commercial Bank in Geneva. In 1962, he becomes Director of Arab People’s Bank in Algeria. Husseini, still in Germany, is appointed to President in Absentia of Fourth Higher Committee of Arab League. http://www.fireandreamitchell.com/2011/02/16/peanut-head-jimmy-carter-claims-the-muslim-brotherhood-is-nothing-to-be-afraid-of/ Muslim Brotherhood unites with Hitler’s Third Reich 1933-2002 http://www.tellthechildrenthetruth.com/mbhood_en.html#part2

Comrade

David Brock in his The Seduction of Hillary Rodham (452 pp. New York, The Free Press) recounts, in absorbing detail, H. Rodham’s transformation from campus radical to Watergate investigator. In her early years Mr. Brock uncovers numerous ties to left-wing, even Communist causes. “We are building a communist organization to be part of the forces which build a revolutionary communist party to lead the working class to seize power and build socialism. [...] We must further the study of Marxism-Leninism within the WUO [Weather Underground Organization]. The struggle for Marxism-Leninism is the most significant development in our recent history. [...] We discovered thru [sic] our own experiences what revolutionaries all over the world have found — that Marxism-Leninism is the science of revolution, the revolutionary ideology of the working class, our guide to the struggle [...]"

the Muslim Brotherhood Flag

The Quartet's Dream

http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/144942 Senators Challenge Obama on Foreign Policy on Israel Sivan 13, 5771, 15 June 11 03:13, by Elad Benari (Israelnationalnews.com) Several U.S. senators have decided to challenge President Barack Obama’s policy towards Israel by introducing a resolution that opposes any Israeli withdrawal to the indefensible 1949 armistice lines. The resolution was introduced last Thursday by Republican Senator Orrin Hatch from Utah and independent Senator Joe Lieberman from Connecticut. “It is contrary to United States policy and our national security to have the borders of Israel return to the armistice lines that existed on June 4, 1967,” the resolution states. It calls Israel “a liberal democratic ally of the United States” and notes that it has been “repeatedly attacked by authoritarian regimes and terrorist organizations that denied its right to exist.” It then acknowledges that the United States Government “remains steadfastly committed to the security of Israel, especially its ability to maintain secure, recognized, and defensible borders; Whereas the United States Government is resolutely bound to its policy of preserving and strengthening the capability of Israel to deter enemies and defend itself against any threat.”

Picture from national Holocaust Memorial Museum

Cartoon from Gaza

NEW YORK – Passengers on a US-flagged boat, The Audacity of Hope, spoke at a press conference Monday to discuss their plans and reasons for joining the “International Freedom Flotilla II – Stay Human,” a flotilla intended to break the Israeli naval blockade of Gaza. It is estimated that people from more than 20 countries will participate in the eight to ten boat flotilla, which will sail the last week of June, in part from Greece. One quarter of the participants on the US boat, which will have 36 passengers, are American Jews. REPORT: Israel readies for Gaza flotilla despite IHH withdrawal Despite IHH pullout, Israel on high alert for flotilla According to a letter the Audacity of Hope group sent to US President Barack Obama, in addition to 36 passengers, 4 crew members, and 10 members of the press, the US-flagged boat “will carry thousands of letters of support and friendship from people throughout the US to the women, children and men of Gaza. There will be no weapons of any sort on board." "We will carry no goods of any kind for delivery in Gaza," the group's letter read. "Our mission is from American civil society to the civil society of Gaza. We do not serve the agenda of any political leadership, government or group. We are engaged solely in non-violent action in support of the Palestinian people and their human rights.”

Zuckerberg's Intifada

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/06/21/us-palestinians-israel-apple-idUSTRE75K5NH20110621 Israel asks Apple to remove intifada phone app 2:32pm EDT JERUSALEM (Reuters) - An Israeli minister has asked Apple Inc to remove an Arabic-language application from its iTunes store that calls for a Palestinian uprising. In a letter to Apple CEO Steve Jobs, Public Diplomacy Minister Yuli-Yoel Edelstein said the application "ThirdIntifada" -- a reference to a future Palestinian uprising -- passed on information about protests, some violent, planned against Israel. "I am convinced that you are aware of this type of application's ability to unite many toward an objective that could be disastrous," Edelstein wrote in the letter seen by Reuters. The application offers users a stream of news stories and editorials in Arabic, announces upcoming protests, and includes links to nationalistic Palestinian videos and songs. Edelstein said the developers of the application had opened a similar page on Facebook three months ago that called for an uprising against Israel through the use of lethal force. Edelstein said he complained to the social network which removed the page. Israel has faced two large protests in recent months that turned deadly when Palestinians in Syria and Lebanon, spurred on by calls over the internet, tried to breach its borders. Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon said the creation of the Apple application and the Facebook page marked a new pattern in attempts to provoke violent attacks against the state. "Companies like this that have a global reach also have a responsibility, and they are aware of this responsibility, and I am sure that Apple will act in the same way (as Facebook)," Ayalon told Israel's Army Radio.

The darwinian Patron Saint of Palestine

The Palestine mandate Flag with the British solar cross and the sun

Prayer to the sun god at Stonehenge, the Temple of the Druids and Masons

Osama Bin laden Dead

Israel's enemies have been so successful at spreading their lies that fewer people all the time recognize the truth. Many college campuses are hotbeds of anti-Israel agitation. Young people are being taught that Israel is waging a genocidal campaign against Palestinians. President Obama has made it clear that his heart is with the Arab world, not with Israel. More liberal "intellectuals" than ever believe that Israel's very existence is illegitimate, and that it is a "fascist state" designing a "new Holocaust" for the Palestinians. American Jews, long caught between their leftism and their loyalty to Israel, are increasingly moving over to the dark side, helped along by organizations like the George Soros-funded J Street that pretend to be pro-Israel while pushing policies that would destroy Israel in short order. It gets worse: "Anti-Israel" has come be a code word for anti-Jew, not just in the Middle East, not just in Europe, but in the United States of America.

The Pentecost under the sungod Surya instead of YHWH

The United States in Burka

An extremist Muslim cleric is planning a March rally at the White House in hopes of sparking a revolution that would turn the United States into an Islamic state. According to the Daily Mail newspaper, Anjem Choudary told a reporter that "The event is a rally, a call for the Sharia, a call for the Muslims to rise up and establish the Islamic state in America." Sharia is Islamic law, and Choudary says he expects the March 3 rally to draw thousands of supporters. The event will be sponsored by the New York-based extremist group Islamic Thinkers. Choudary is a British cleric who said insisted that one day "the flag of Islam will fly over the White House" and that Americans "are the biggest criminals in the world today."

They say, Islam will conquer the world

Hamas Jugend

Fatah 11

The Geocentric Seal of Kansas

The Al-Qaeda SS

On January 16, 2011, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) released the fourth issue of its English-language magazine, Inspire. In the latest issue, AQAP redoubled its efforts in inciting Muslims living in the West to become jihadists and carry out attacks against civilians in the countries of their residence.

In a speech yesterday in Dearborn, Michigan, the former White House correspondent not only defended the earlier anti-Jewish remarks that led to her sudden resignation, but went on to claim that she was made to pay a price for her remarks because of the power of the Jewish lobby in the United States. Helen Thomas has nothing to say about the 1 million plus Mizrahi*/Sephardic Jews who were from Arab lands until they were shoved out. No, she hasn’t anything to say about these Jews, she buys into the myth that all Israelis are European Ashkenazi Jews. What an anti-Semite, and to think that turd was/is given front row seats to all the WH press conferences.

The Fathers of Modern Atheism

Philosopher M. Polanyi observed, “Newtonian physics and Darwin’s notion of the survival of the fittest were key elements both in the Marxist concepts of class warfare and of racial philosophies which shaped Hitlerism and scientific world view.” And we focus attention and concern on the Jewish Holocaust because somehow we all have the feeling that it might just happen again.

WikiLeaks Watchers over Democracy

After the WikiLeaks

Russian President to visit Israel in 2011

Russia’s President Dmitry Medvedev plans to visit Israel in early 2011, Israel’s Ambassador Dorit Golender told reporters on Monday. She said Israel is regarding the visit as a part of the multidimensional development of Russia-Israel relations. The president will visit the city of Netanya to lay down a monument to Soviet WW2 soldiers. The visit may also result in transferring Jerusalem’s Sergei’s Courtyard to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Business as usual

The trucks, with their load of 20,000 roses and five tons of strawberries, left through Kerem Shalom crossing in southeast Gaza. Mahmoud Khalil, a representative of farmers, said the agricultural products would be sold in the European markets, mainly in Holland.

Picture of an early Christian from the catacombs

Notice the swastikas on his dress

Jerusalem The Old City

Tea Party

Swastika Koran

Gorbachev: Victory in Afghanistan is impossible

Former Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev has said that NATO troops will never achieve victory in Afghanistan. The republic should be assisted in overcoming the aftermath of military operations, Gorbachev told Moscow-based BBC correspondent Steve Rosenberg. He also praised U.S. President Barack Obama for his decision to start withdrawing troops next year, adding that before the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan, an agreement had been reached with Iran, India, Pakistan and the U.S., providing for Afghanistan’s becoming a neutral, democratic country

Deauville Summit Supports the Talks

Statue of Confucius, Father of Chinese geocentrism goes up in Russia

The ideal prince of China rules by moral force (te) contrasted with li “physical force”; he is compared to the “north polar-star, which remains in its place while all the lesser stars turn about it.”

Shimon Peres meets guests from China

Israel's President Shimon Peres (2nd R) receives a gift presented by Huang Huahua (3rd L), governor of south China's Guangdong Province, during their meeting in Jerusalem, Oct. 24, 2010. (Xinhua/Yi Dongxun)

the Ice Crystals of Auschwitz

Death Fugue

Anna Chapman, a Russian Spy receiving Top Honor

The Russian spies who were deported from the US in the biggest spy scandal since the Cold War have been awarded top state honours by Dmitry Medvedev, the Russian president.The awards were handed out at a Kremlin ceremony on Monday, less than four months after the exchange, Natalya Timakova, Medvedev’s spokeswoman, said. No television footage or pictures have so far been released of the ceremony. J. Pollar still languishing in US Jail. No mercy for Jews.

Al Turki in Bejing

Jia Qinglin (R), chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, talks with Abdullah Al-Turki (L), secretary-general of the Muslim World League in Beijing, capital of China, Oct. 14, 2010. Jia met with a delegation of the Muslim World League headed by Abdullah Al-Turki on Thursday. (Xinhua/Ma Zhancheng). More than 120 delegates from 18 religions gathered Sept. 24, 2003 in Kazakhstan’s political capital to condemn terrorism and lay the foundations of an organization they advertised as a diverse effort to reduce violent clashes between faiths around the world. Envoys who attended the conference included Sheikh Abdullah al-Turki, secretary of the Muslinm World League based in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, Yonah Metzger, Ashkenazic chief rabbi of Israel, Cardinal Josef Tomko of the Vatican. “Violence and terror can only come to an end if we promote religious values on a global scale,” Ayataollah Mahdi Hadavi, professor of Islamic law at Qum Seminary School and head of the Iranian delegation, told the conference. More than 120 delegates from 18 religions gathered Sept. 24, 2003 in Kazakhstan’s political capital to condemn terrorism and lay the foundations of an organization they advertised as a diverse effort to reduce violent clashes between faiths around the world. Envoys who attended the conference included Sheikh Abdullah al-Turki, secretary of the Muslinm World League based in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, Yonah Metzger, Ashkenazic chief rabbi of Israel, Cardinal Josef Tomko of the Vatican. “Violence and terror can only come to an end if we promote religious values on a global scale,” Ayataollah Mahdi Hadavi, professor of Islamic law at Qum Seminary School and head of the Iranian delegation, told the conference.

Chinese Vice Premier Hui Liangyu delivers addresses the opening ceremony of 2010 China (Ningxia) International Investment and Trade Fair and the First China-Arab States Economic and Trade Forum in Yinchuan, capital of northwest China's Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Sept. 26, 2010. (Xinhua/Liu Quanlong)

The Spider Net

JFK and W. von Braun, SS Major

In May 1961, Kennedy issued the challenge: "First I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

http://www.angloisrael.com/

In God We Trust - Tea Party

Tea Party on the Horizon

Give them an ultimatum Sept.16,2010

Syria has demanded that Israel agree in principle to relinquish the Golan before talks begin, a demand that Israel has rejected. Israeli leaders say Syria must ends its ties with Iran and with PA-based terrorist groups such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad. And the PA demands that Israel agree in principle to relinquish Judea and Samaria before talks begin. So what to talk about? Well, they want the whole Israel between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. And that's their idea of the “peace”

NYT Cartoon: Expect the worse

Goal of Science – Nobel Laureate in Physics, Steven Weinberg, stated: “Nothing has been more important in the history of science than the work of Darwin and Wallace”. He pointed out that “not only the planets but even life could be understood in this naturalistic way.” He added: “I personally feel that the teaching of modern science is corrosive of religious belief, and I'm all for that! One of the things that in fact has driven me in my life, is the feeling that this is one of the great social functions of science – to free people from superstition”. … “The Ten Commandments portray a deity who is self-centered, selfish, jealous, obsessed with his own importance; this is not a nice kind of person. The traditional teachings of religion are, from the point of view of the morality most people share today, pretty immoral”

Here are some further quotations from Peter Singer from his books Rethinking Life and Death and Writings on an Ethical Life.On how mothers should be permitted to kill their offspring until the age of 28 days: "My colleague Helga Kuhse and I suggest that a period of twenty-eight days after birth might be allowed before an infant is accepted as having the same right to life as others." Brahmins also treat their own children as untouchable. Brahmin mothers dont touch their own children and brahmin mothers also dont love their children. What a horrible people these brahmins are.

Burka

When have American academics and theatre people last refused to travel to, buy products from, or lecture, appear in performance in Jordan (clothing, manufactured goods), Egypt (oil, textiles, cotton), Saudi Arabia (oil), Turkey (oil, metals, textiles, manufactured goods) or Pakistan (textiles, manufactured goods)? Surely the human rights records of these countries cry out for free people of goodwill to do just that in response to the large number of honor-related crimes, including honor killings, the forced veiling of women, persecution of Christians and other infidels, the torture and imprisonment of artists and dissidents, the non-stop Islamist terrorist attacks against Muslims, and the “manufacture” and distribution of the most vicious propaganda against Israel and America.

Martyrs Brigaes in action

NEW DELHI — Kashmir erupted on Monday in the worst violence since separatist protests began sweeping through the disputed Himalayan region three months ago, with authorities partly blaming the inflamed tensions on televised reports of Koran desecration in the United States. The bloodshed, which came as Indian leaders were searching for a way out of the Kashmir crisis, left at least 14 civilians and two security officers dead and at least 60 people injured in clashes across the region, authorities said. In one town, Tangmarg, authorities said officers opened fire after protesters had set a school and other government buildings ablaze.

German Award for the Muhammad Cartoonist

Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard (left) is congratulated on his prize by German Chancellor Angela Merkel (right) and Joachim Gauck, a former human rights activist in East Germany, during the award ceremony Wednesday.

+chief+of+general+Staff+of+PLA+meets+with+defense+minister+and+chief+of+staff+of+Kazakhstan.jpg)

Chen Bingde (R), chief of the General Staff of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, meets with Saken Zhasuzakov, first deputy defense minister and chief of the staff of Kazakhstan's Armed Forces, in Almaty, Kazakhstan, Sept. 9, 2010. Chen visited Almaty on Thursday to attend the opening ceremony of the "Peace Mission - 2010" anti-terrorism military exercise, which is launched under the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in south Kazakhstan from Sept. 9 to 25. (Xinhua/Wang Jianmin)

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) greets Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas (L) and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as leaders gathered to deliver a joint statement on Middle East Peace talks in the East Room of the White House in Washington September 1, 2010.

Abbas resembling Einstein